Objectivism and Subjectivism in Philosophical Context

Deconstructing a Facebook Debate

I wrote this years ago for a course I was teaching, and after discussing subjectivism on the recent podcast with Stace, I thought people might find it useful.

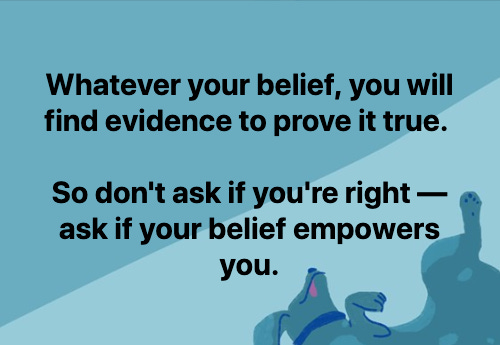

I broke my own rule of not engaging in debate, because almost always when I go looking for an intellectual discussion, I end up disappointed and sad. So it must be said that I am not a victim here, and my contribution to this drama is the following: the poster of the image shown below is a new friend of mine who is also a coach. I have agreed with everything he’s ever posted prior to this and was excited to find someone who saw the world a lot like I did–that’s rare for me.

So when he posted the below, I unconsciously got worried I had misjudged him and engaged in a debate to try to make other people make more sense. So I came in part, from fear. This is a pattern that goes back to my childhood and the suffering I endured as a result of being more conscious and intelligent than my parents at an early age. This childhood challenge is part of what forged me into a teacher, as I tried to show my parents how to parent me, which of course inevitably fails. This is fairly common, although largely unseen.

So while in context, I got what I deserved: feedback about my motives and the futility of debate. In content, I was right in a way that is fascinating to explore, and gave me a great puzzle for us to work on, a solid consolation for the stress I caused myself.

Take as much time as you need to follow each step and the logical connections. If it’s very difficult, don’t worry. Remember that working on problems you can’t yet solve is the best way to learn. Stretch yourself. Here’s what my Facebook friend posted:

I was the first to comment on the thread. A number of people oohed and ahhed at the purported wisdom. Here is a selection of what else happened with some commentary.

Josef: Is it more important that it empowers you than being true?

Person A replies to me: “Either sounds like a recipe for local optima for me, the question frame implies they trade-off against one another.”

A “local optima” means “the best relative solution to a problem.” (I had to google it) So the assertion here is if you are faced with the question of what is true vs. what empowers you, then it makes more sense to go with the latter. (About his trade-off assertion about my question. I implied that it can, not that it always has to. What’s the problem?)

For example, you can’t decide whether to marry Jane or Diane. You don’t know what’s true, so you go with which relationship makes you feel more powerful. Certainly, this is useful in some cases. But as you’ll see there are some limits to this idea. That might be because Diane sees your gifts, or it could be that Diane lets you dominate because she’s so weak. Notice how Person A did not answer my question, which asked for a “Yes” or “No” (which I did on purpose).

Can you think of cases where basing a choice on what empowers rather than what is true could be problematic? Stop and think of a few, this is how you’ll learn.

Original poster replies to me: “One way or another, you’re going to create it true. True is another flavor of ‘right’ in this context. So, it doesn’t really matter if it’s ‘true’. That’s the point.”

This is important and subtle. You may not realize it, but the poster is asserting an enormous premise about the nature of reality here. To be able to debate this point, you must be able to see the implicit assumptions he’s asserting as truths here:

Objective truth is either totally unknowable or irrelevant to human beings because of how the mind filters reality to validate its beliefs

Therefore, we live entirely in a subjective reality of our own mind’s creation, so we might as well make it up to be whatever makes us feel powerful

This is going to take us on a bit of a journey, but it could change the way you see things forever, if you take this in deeply. The question of objective reality vs. subjective is one of the cornerstones of the history of the pursuit of truth. Every religion, philosophy, and spirituality answers this question in one way or another, though most people can’t think paradigmatically enough to appreciate this. This is why it’s important to deconstruct. You could be living, right now, somewhere on the subjectivity spectrum, probably without realizing it. When you can see where you are, you have the power to do something about it.

Objective reality means there is an absolute way things are. Mainstream religions were all founded in objectivism. In Christianity, for example, there is a heaven, a hell, a God watching us all, his son who died for our sins, and we behave according to certain standards we earn life ever-lasting. That’s how it is, there’s no negotiating with it.

There are variations depending on the sect, but the structure is the same. You’ll notice that the rigidity of the rules of religions has softened over the last hundred years. For example, in 2013 Pope Francis said “If a person is gay and seeks God and has goodwill, who am I to judge?” strongly implying that homosexuality was no longer a sin without taking any firm stance on the matter. (Chicken!)

However, in 2015, he said that “the family is threatened by growing efforts on the part of some to redefine the very institution of marriage” and suggested that same-sex marriage “disfigures God’s plan for creation.”

Okay, so it’s not for anyone to judge homosexuals...but if they want to get married that’s anti-God? That’s still okay to judge, then? Or God can judge, but we can’t? Do you see the muddiness and logical contradiction? What’s most remarkable is how many people are willing to operate in such a muddled area.

It would be more coherent, rigorous, and in integrity to either maintain that homosexuality is a sin, or admit the church has persecuted homosexuals for thousands of years and reverse its stance entirely. The reason it’s changing slowly serves its existing members’ fear of change. Wherever you see a lack of reason, there is almost always fear at work. This is why paradigmatic analysis is so powerful. It’s a tool to ferret out the fear that causes us to distort reality.

We’re in pure critical thinking territory here, where coherence is most important. It doesn’t matter what you think about Christians or gays. In fact, I use these potentially controversial subjects precisely to challenge people to think clearly about it. Whether you’re pro or anti-gay, you cannot argue with the Church’s lack of clarity above, do you see? Whether you’re pro or anti-Christian, you cannot argue with the fact that Christianity is an objective model. Objective here doesn’t mean “impartial,” it means it attempts to state the absolute nature of reality.

To think clearly, you have to make coherence and clarity more important than your beliefs and opinions. You have to be willing to be wrong, feel stupid, and embarrassed at any moment.

None of us knows everything, and all of us are learning, so what’s the problem? In fact, a moment where you feel stupid is inevitably followed by profound learning, right? A mature person can enjoy the feeling of being stupid with enough practice, because they know that losing false ideas is how you get smarter, and their desire to have a coherent picture of reality is more important than their temporary discomfort.

The fundamental assumption of critical thinking (of which paradigmatic analysis is a part) is that the truth is coherent. It’s whole. It has a natural integrity to it. We know this instinctively. This is why children in Sunday school ask questions like, “Could God create a rock so big that he couldn’t lift it?” and “Why does God let bad things happen to good people?” As humans, we have an innate desire to make sense of our world in a coherent way, and there are good reasons for this. When our thinking is coherent and clear, we tend to make better decisions that lead to favorable outcomes.

So now you know what an objective model is, and this includes paradigms like mainstream Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, as well as secular models like psychology, biology, chemistry, etc.

Whereas an objective paradigm says, “There is a way reality is and it doesn’t matter what you (subjectively) think?” a subjective paradigm says, “Reality is what I think it is.” How far this goes depends on the paradigm.

To fully appreciate how subjectivism operates today, we need to review some history.

Human beings learned about the mischief that extreme objectivism causes between about 500 B.C. and through the middle ages, in the western world. Most of the world during this time was run by people who claimed they should rule because whatever divine entity of the area said so. In medieval France, this actually included a guy who claimed he descended from a godlike sea monster!

The governing paradigm of this period was objectivistic, do you see? Your opinion of yourself, your skills in leadership, your experience, etc. didn’t matter. What mattered was an objective standard that fit the prevailing objective pictures of the world.

It’s easy for us to laugh at this, but the people of that time would equally laugh at our democratic attempt to elect leaders with constantly changing, undefined criteria, hugely influenced by subjective media coverage and the fickle nature of perception. Can you see it from that point of view?

The more you look at our system the more a leader ordained by God may start to make sense...if you could get yourself to believe the paradigm that supports it.

Now you’re exercising your paradigmatic analysis muscles!

The objective paradigm of the Catholic Church created deeply classist societies, where the special, allegedly God-chosen folks enjoyed lavish lifestyles financed by the working class who paid the Church to tell them what was what and absolve them of sin so they would be rewarded when they died.

A clever racquet, isn’t it?

And don’t forget it was during this thousand-year period that holy wars, torture, and other mayhem occurred, resulting in the fact that more people have been killed in the name of God than anything else.

You can imagine that after a while, the situation looked bleak for the commoners (who were fighting the wars or losing their husbands), especially as the elite grew richer and the serfs poorer. Resistance to the Church in Europe culminated in Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, founded on some very individualistic/subjectivistic tenets.

Two of the tenets continue to echo forward into today. And remember, the United States was founded by Protestants, and (for a bit longer perhaps) is seen as a cultural leader in much of the world.

Sola scriptura “by Scripture alone”

The Bible can and is to be interpreted through itself, by individuals. The invention of the printing press around 1500, meant that people could afford their own copies of the Bible, and so interpret its meaning on their own. This radically decentralized the power and authority of the Church.

Sola fide “by faith alone”

This tenet asserts that good works are not a means or requisite of salvation. This undermined the aristocracy’s scheme to get lower classes to work for them as a means to get into heaven. It recasts work itself as being an individual, secular issue and not an obligatory service to God. This is a critical shift in world history about the nature of work, and the moment when work (in theory anyway) shifted from being other-serving to self-interested.

As literacy spread, the Catholic Church weakened, and a middle class emerged. A hunger for discovery awakened in the people of Europe. New libraries facilitated access and ideas once forgotten as far back as ancient Greece were reawakened. Feudal lords were replaced with centralized governments that cared at least a little bit more about the welfare of people.

This was the heart of the Renaissance. But the monarchies that replaced feudalism would eventually all be displaced by democracies by the 19th century precisely because of the rise of individual rights. There were hundreds of smaller rebellions and revolts between 1500 and 1900. We generally only think of the big ones like the French Revolution (1789) and the American Revolution (1765-1783).

The United States remains to be the only country in the history of the world founded on individual rights, precisely because it was founded so late in history. Consider this for a moment: prior to 250 years ago, no collective entity in history was ever fundamentally about the freedom and happiness of the individuals.